EFFIGIES — Bringing nerds together to reveal the hidden wisdom of comics for fuller, more productive lives!

What’s Inside:

The 1 in 60 Rule.

What is feedback and why is it important?

Distinguishing signal from noise.

Why frequency of feedback matters.

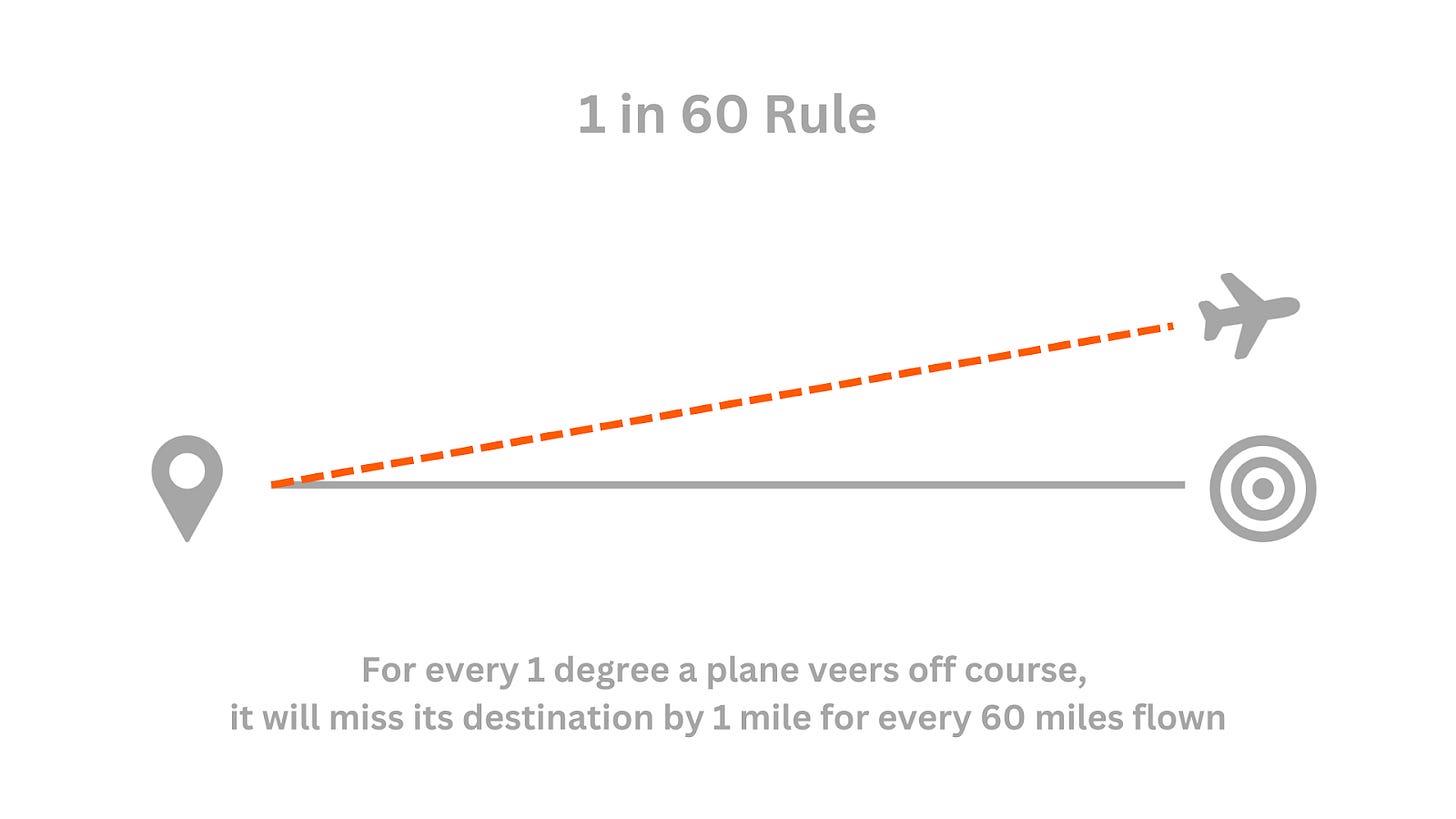

What is the ABC method of goal-setting?Here’s a concept that’s always on my mind: in aviation, there's a principle known as the "1 in 60 Rule." It states that for every 1 degree a plane veers off course, it will miss its destination by 1 mile for every 60 miles flown. This small deviation can lead to a massive detour if not corrected early on. The same concept applies to personal and professional growth, where feedback acts as your navigational tool, keeping you on course toward your goals.

Whether you’re honing a skill like writing dialogue, working on a larger goal like getting in shape, or simply trying to improve in some area of your life, feedback provides the insight needed to adjust your approach and make meaningful progress. But what exactly is feedback, and how can you use it most effectively?

Note: Stick around to the end for a case study in feedback featuring the in-process cover for No Heroine 2 #1!

What is feedback?

Feedback is information provided about your performance or work, helping you understand where you stand relative to your goals. In the context of making comics, writers and artists receive feedback from editors. Editor feedback can include comments on a script, suggestions for improving panel layouts, or critiques of dialogue and character development. The key aspect of feedback is that it offers an external perspective or crucial data that acts as a guide to keep you on target, regardless of your goal.

Why is feedback important?

Feedback is crucial because, without it, you might miss critical (or even minor) issues that could undermine your efforts toward achieving your goal.

An editor’s feedback, for example, can point to solutions writers might not be thinking about. When I was writing Power Rangers Universe: Edge of Darkness, I had written a climactic fight sequence that played out as the emotional arc of the story was peaking, but in the first couple of drafts, it just wasn’t hitting the way I wanted. Then I received an editorial suggestion to cut most or all of the dialogue. I took the note, and on the next pass, the action and emotional beats played out much better because they weren’t competing with dialogue that wasn’t adding anything extra or meaningful. That small note helped me course-correct and achieve the effect I was aiming for.

In my case, I was trying to do too much and ended up stepping on my own toes. You might be doing too little, or perhaps you’re taking the wrong approach. Feedback can help you recognize when your efforts are standing in the way of your goals and open avenues for altering your behaviors to better align with those goals.

Signal vs. noise.

Unfortunately, not all feedback is created equal, and knowing which feedback is useful is invaluable. One of the challenges in utilizing feedback effectively is distinguishing between signal (valuable, actionable insights) and noise (irrelevant or overly subjective opinions). Signal is the feedback that directly relates to your goals and offers clear guidance on how to improve. Noise, however, might come in the form of overly critical or vague comments that don’t necessarily contribute to enhancing your efforts.

To maximize the effectiveness of feedback, it’s important to filter out the noise and focus on the signal. This means considering the expertise of the source of your feedback. If you’re trying to shed a few pounds, your scale can be a source of noise or signal, depending on how you use it.

Using daily weigh-ins to determine your diet’s success can produce a lot of noise. Factors like water weight fluctuations or a big meal could impact the results on the scale. This feedback may cause you to correct or change behaviors when there is no need.

This feedback is noise.

Conversely, tracking your weight daily, taking a weekly average, and then comparing averages across weeks can give you a much clearer picture of your actual progress. Zooming out like this helps eliminate the daily feedback (noise) that could lead to potentially counterproductive adjustments to your approach.

This is signal.

Frequency of feedback.

If you know your feedback is signal, you should focus on increasing the frequency of feedback. Regular feedback allows you to make incremental adjustments along the way rather than at the end.

Consider the difference between getting feedback on a few script pages or scenes early on and hearing comments only after the entire issue has been sent to the printer. Early editor feedback can shape the narrative and help the artist tweak visual elements before they’re set in stone. But feedback after the print files are finalized? Useless—it’s too late to change anything.

This is an extreme example, of course.

Looking back at the weight loss example, we see how frequent feedback is valuable. By taking weekly averages and comparing them regularly, you can quickly determine if your efforts are working. If your weight is down week-over-week (WoW), you’re on the right track and should keep it up. If it’s up, you can review your daily data to find the cause—perhaps a few big dinners? If the WoW average increases, it’s a clear sign you need to adjust your approach to stay aligned with your goal.

Now, imagine you’re only looking at your monthly averages, and this month’s average is higher than last month’s. Getting feedback every 4 weeks instead of every 1 week means that if your approach is counterproductive, you’re finding out every 28 days rather than every 7 days.

Let’s revisit the “1 in 60 Rule” to illustrate why frequency matters so much:

If you weigh yourself weekly, you can make small adjustments based on fluctuations in your weight. Over the course of a month, these minor adjustments help keep you on track. With the monthly approach, on the other hand, the slight gain might go unnoticed until the end of the month. Without timely adjustments, you risk drifting further from your goal.

Framework for effective feedback.

We’ve covered a lot so far, but luckily all of that information boils down into a simple framework. To maximize the value of feedback, follow these three simple rules:

Seek Feedback - Leverage feedback as you work toward your goal. Seek out sources of input, such as data or outside perspectives, that can help you stay on track and course-correct if you are off course.

Filter Feedback - Not all feedback is useful feedback. It’s important to distinguish between valuable (signal) and less relevant (noise) feedback. Prioritize actionable advice that aligns with your goals and ignore feedback that doesn’t contribute to your vision.

Increase Feedback Frequency - If you’re sure your feedback is all signal, strive to increase the frequency of your feedback. Regular check-ins allow for early corrections and continuous improvement through small, manageable changes.

As you work toward your goals, remember that feedback is your compass. It guides you, helps you make necessary adjustments, and keeps you on course, whether you're writing your next story, striving for better health, or pursuing any other goal. Embrace it, filter it wisely, and seek it out regularly—because with the right feedback, you can navigate your way to success.

- Frank

I’m Frank Gogol, writer of comics such as Dead End Kids, No Heroine, Unborn, Power Rangers, and more. If this newsletter was interesting / helpful / entertaining…

You can also check out some back issues of the newsletter:

After credits scene.

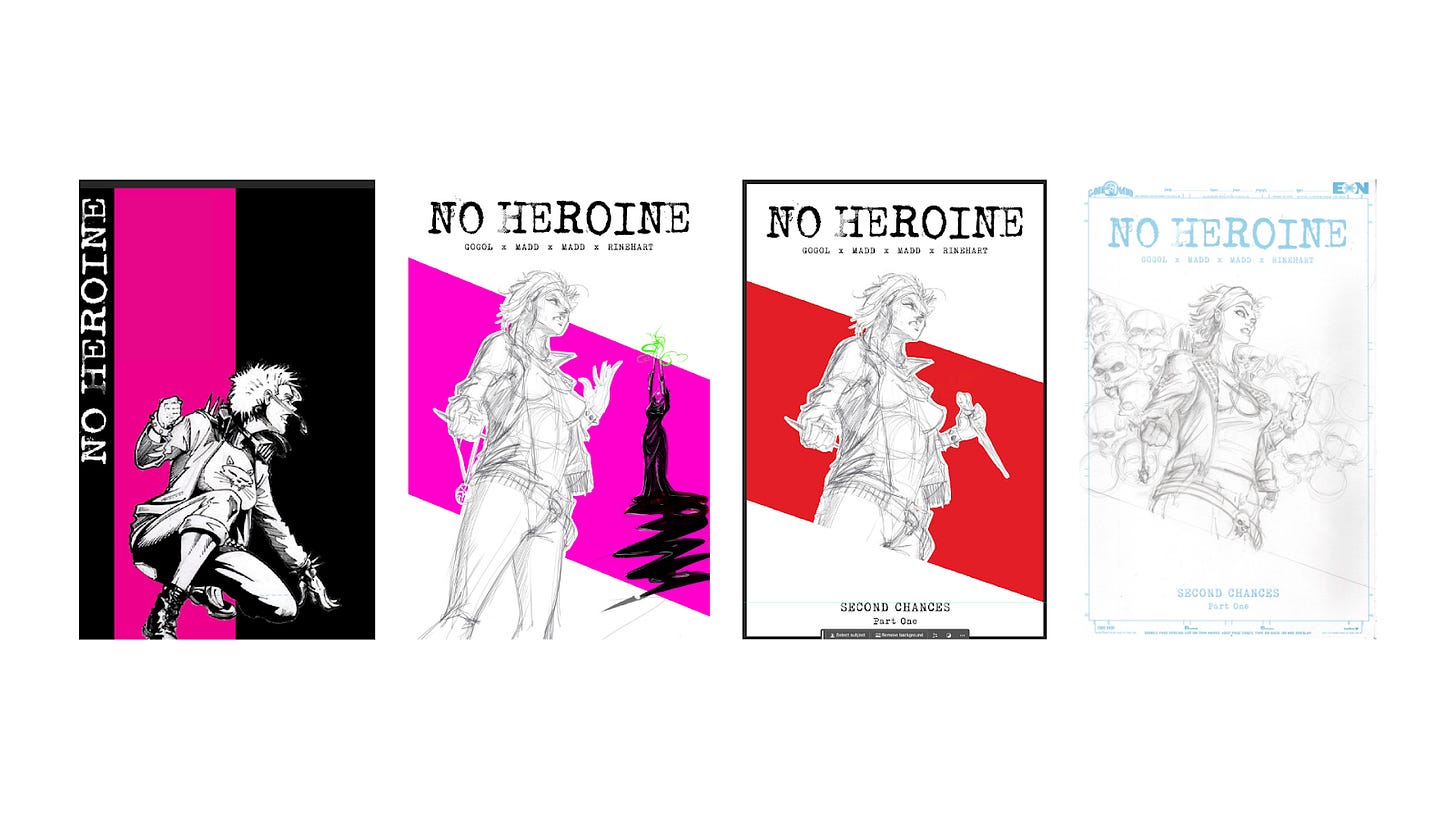

Over the past week, I’ve been collaborating with Criss Madd, the artist of No Heroine, on the cover for the first issue of the new series. This process has been a perfect example of the feedback loop, with Criss and me brainstorming and refining the design at each stage. Here’s a sneak peek:

In the first image, we have a mockup I made in Photoshop using some existing art and the branding for the book. Criss and I then hopped on the phone and decided to go with branding more like the original series, and Criss mocked up some original art for the cover. From there, we discussed further and made more tweaks. In the final picture, you can see Criss’s in-process pencils for the final cover. In this series of images, you can see how feedback helped us move from concept to near-final product, and how check-ins along the way helped us hone our shared vision and get closer to the goal of having a finished cover.